Updates

EMS WORLD Article: Blood on Demand: Designing an EMS Massive Transfusion Program

EMS WORLD: SEE FULL ARTICLE HERE

04/25/2019

Issue:

Dan B. Avstreih, MD, FACEP, FAEMS; John I. Morgan, MD, FACEP; and Craig Evans, BA, EMT-P

In September 2017 EMS personnel in Loudoun County, Va., responded to a severe crash involving a converted bus and a passenger vehicle. The bus—a school bus transformed into a food truck—t-boned a late-model station wagon on the driver’s side, pushing it into a ditch, pinning it against a guardrail, and coming to rest on top of it.

The crash resulted in five critically injured patients with heavy entrapment and limited access. They required a complex rescue with a large number of EMS and fire responders, including crews from four helicopters. A lengthy extrication ensued, with concern for ongoing blood loss in the critically injured. All blood products from the responding helicopters were utilized, and crews anticipated the need for more blood.

Utilizing on-scene physician medical direction, a request was made to local hospitals to send additional blood to the crash site. Several facilities mobilized blood products, which were sent in coolers via both law enforcement and fire and rescue. Rescuers used this blood in the continued resuscitation. The four patients who survived initial impact were finally extricated and transported to the local Level 1 trauma center for definitive care, and all survived to eventual discharge.

The Aftermath

EMS physicians from Loudoun County and neighboring Fairfax County began discussing the potential for an EMS blood supply the very next day. Both tailboard and after-action reviews of this incident highlighted the need for a more streamlined and formalized process for requests of this nature in the region. Ultimately this led to the development and implementation of the Field-Available Component Transfusion Response (FACT*R) program.

There were four main groups in the coalition: EMS agencies, the local EMS council, the hospitals, and blood-donor services. The Fairfax County Fire and Rescue Department and Loudoun County Combined Fire and Rescue System are both combination career/volunteer fire-based EMS systems fielding a total of 2,600 operational personnel (700 ALS providers) and serving a population of 1.6 million over 920 square miles of urban, suburban, and rural areas. The Northern Virginia EMS Council is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization tasked by the state with the development and implementation of an efficient and effective regional EMS delivery system across 13 EMS agencies and 12 hospitals representing six hospital systems.

There are currently two major health systems with high-level trauma centers in the region, as well as several other hospitals and freestanding emergency departments. Ultimately the tertiary-care/Level 1 trauma center served as lead for the hospitals, with a Level 3 trauma center from the same system also serving as a program site. Most of the blood products utilized by hospitals from all systems in the region come from this health system’s blood-donor services, which include the largest hospital-based blood bank in the United States.

The coalition’s goal was to make trauma bay-level, high-ratio, massive transfusion protocol (MTP) blood-product resuscitation available to EMS providers for critically injured patients in hemorrhagic shock. The program is not meant to replace, nor would it exclude, any plan to stock blood products on frontline EMS units. In fact, both the skills and relationships from a collaboration like this will likely facilitate moves to carry blood or blood products for standard operations in the future.

Early in the development of the program, the FACT*R coalition conducted a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis to help shape design and implementation strategies. Challenges fell into four main categories: the blood, transfusion equipment, usage protocols, and training.

The Blood

Literature suggests patients in hemorrhagic shock do better when lost volume is replaced with either high-ratio blood products or whole blood. Many hospitals have massive transfusion protocols for rapid deployment of large volumes of blood products, leading to the choice of five units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), five units of fresh plasma, and a five-pack of platelets at each FACT*R site. Paramedics are permitted to start and maintain blood under Virginia EMS regulations; however, blood products are expensive, highly regulated, have limited shelf life, and can be scarce.

Furthermore, while the region’s largest blood supplier is connected to a health system, the operational managers of blood services had no opportunity for working relationships with EMS other than periodic collaboration hosting blood drives. The EMS physicians, who had regular experience with hospital blood-product protocols as well as EMS systems, were a critical bridge with the hospital and blood-services stakeholders.

Over the pre-implementation phase, program leaders met with hospital committees on trauma, emergency medicine, anesthesia, critical care, blood utilization, and quality to ensure awareness and buy-in from the health systems. Since EMS agencies billed patients according to treatment level and not for itemized individual supplies or medications, the health system’s legal and financial representatives agreed it was reasonable not to charge the EMS agencies for program activation or contents.

The biggest concerns from blood services were regulatory compliance and appropriate use of resources. The EMS protocols developed utilized tight physiologic criteria for hemorrhagic shock. Training explicitly called for a shift in mind-set for this protocol from the more common “get wheels on the road” to one of “is this the call?” In contrast to usual physician online medical direction, which is provided in our region by the physicians on shift at the receiving emergency departments, activation of the FACT*R protocol required real-time authorization from one of the participating agencies’ designated EMS physicians.

A program-specific field transfusion record was collectively developed to facilitate recording and critical cross-checks for emergent blood administration, and serve as a mechanism for postadministration reconciliation. Ultimately the willingness of the EMS physicians to act as both gatekeepers to resource deployment and guarantors of final accountability to blood bank regulations made this program a success.

The Equipment

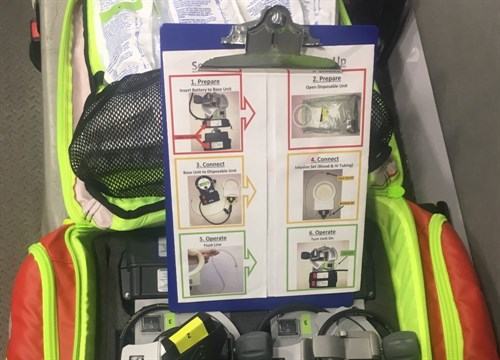

Outside the blood itself, the most significant cost to the program was the compact, battery-operated blood warmers, which employ both reusable and single-use components. To overcome cost barriers during the initial program, we decided to keep the warmers, as well as related tubing and other transfusion equipment, colocated at the facilities supplying the blood. This guaranteed any agency requesting the blood would have all the necessary equipment for administration (as opposed to having to replicate the equipment cache on multiple vehicles across multiple counties) and also meant each cache could have at least two warmers for more rapid dual IV/IO operations.

Multiple funding strategies were considered, including leveraging collective agency dues, existing EMS council funds, and grant funding. Ultimately the coalition employed a novel strategy of partnership with private and corporate philanthropists from the local healthcare space to sponsor the program, which covered virtually all the start-up costs.

The Protocol

The protocol incorporated both clinical and incident considerations, grouped into three key concepts: sick, stuck, and survivable.

Potential patients must have evidence of hemorrhagic shock after initial PHTLS lifesaving interventions, as well as IV or IO access and continuous monitoring (sick). In addition, patients whose mental status is only “unresponsive” on an AVPU scale are likely to have nonsurvivable brain injuries and therefore not candidates for the program (survivable). The Incident Commander or designee from the Rescue Group must strongly anticipate the patient will be entrapped for more than 30 minutes from activation, making it logistically feasible to get the blood packed and to the scene (stuck).

Upon activation by the agency EMS physician, the blood is immediately packed in coolers and pushed to the emergency department, where it, along with the transfusion equipment bag, is transported to the scene by a dispatched public safety asset. O-positive PRBCs are used if the patient is male or over age 50, O-negative if the patient is a female of childbearing age.

If the patient is either transported or expires before blood-product arrival, the coolers are returned unopened to their originating blood bank so the blood can be used in normal hospital operations. All opened blood coolers accompany the patient to the closest appropriate trauma center by agency protocol for administration during transport, even if it’s not the center that supplied the blood.

The Training and Execution

This program addresses a high-acuity, low-frequency event with complex medical and logistical requirements. All aspects of the EMS system, from communications to apparatus to frontline providers, worked to engineer the process to be simple, standardized, and based on best practices in stress performance.

This included color-coded assembly step labels for the transfusion equipment and incorporating pre-administration checklists and “just in time” reminders into the field transfusion record. Checklists were also developed for the EMS agency communications staff and technicians in the blood banks. Fields were added to agency ePCR and blood bank accountability software so the blood-product administration could be appropriately tracked.

Awareness-level training was developed by both agencies in conjunction with hospital nurse educators and blood bank staff, including a detailed 16-minute training video produced and distributed to all local EMS agencies and healthcare facilities. Advanced life support providers, as well as all rescue squad and technical-rescue operations team members, received additional face-to-face and hands-on training. On top of this, the EMS supervisors received extensive operational-level training that included simulated blood products (including exact mockup labels/paperwork), equipment assembly, and scenarios conducted with their medical directors.

We conducted no-notice drills on the process prior to implementation and regularly after go-live. The blood bank staff consistently achieved times from phone call to products on ambulance ramp of 6–10 minutes, far better than the 15-minute benchmark set in the program’s development.

To further ensure accuracy of records, empty bags from any blood products administered are placed in a labeled resealable bag included in the equipment cache. These are ultimately rechecked and reconciled with the field transfusion record by the EMS supervisor prior to appropriate disposal.

Once completed, all records are faxed to the EMS agency and blood bank for integration into the patient’s chart. We anticipated there may be times where the patient’s demographic information may not be immediately available (to save time, critically ill trauma patients are often registered under prepopulated trauma identifiers until their identities can be confirmed and updated by patient registration). To address this, the medical director of the transporting agency agreed to be responsible for the eventual closure of that information loop. Finally, internal quality assurance review for all blood administration was mandated by all participating agencies.

Dan B. Avstreih, MD, FACEP, FAEMS, has served as an EMT, EMS supervisor, and flight physician in his 25 years in EMS. He is board-certified in emergency medicine and subspecialty-certified in EMS. Since 2010 he has served as associate operational medical director for the Fairfax County (Va.) Fire and Rescue Department.

John I. Morgan, MD, FACEP, began volunteering with the Charlottesville-Albermarle Rescue Squad as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. He received his doctorate in 2000 from the university and completed his residency in emergency medicine at Stanford in 2003. Since 2004 he has served as operational medical director for Loudoun County (Va.) Combined Fire and Rescue System and volunteer EMS agencies in the county.

Craig Evans is the Executive Director of the Northern Virginia EMS Council. He began his career as a volunteer with the Warrenton Volunteer Rescue Squad in Warrenton, VA at the age of sixteen. Thirty years later, he retired from The City of Fairfax Fire Department.